This election cycle, presidential candidates have characterized tariffs as both a miracle cure for all economic injustices as well as a potential tool for mass disruption.

President Trump has described potential tariffs ranging from 20% to 2,000%, sometimes saying they would apply only to certain countries or industries and at other times suggesting they might be applied to all imports. Meanwhile, Vice President Kamala Harris has framed these policies as an unavoidable sales tax paid by American consumers.

This month we want to discuss the history of tariffs, how they are applied, and their economic impacts.

A brief history of Tariffs and how they work

A tariff is a tax imposed on the imports or exports of goods. In modern parlance, it is most often used to refer specifically to a charge on imports.

Tariffs have been a documented part of economic systems as far back as ancient Greece, when Athens levied a two percent charge on goods such as grain that arrived through the docks of Piraeus. Tariffs have been widely used throughout history to raise revenue and compete against economic rivals.

In the United States, the Customs and Border Protection agency collects tariffs and transfers the revenue to the U.S. Treasury. Tariffs are typically levied as a percentage of the price a buyer pays a foreign seller.

Before federal income tax was established in 1913, tariffs were a major source of revenue. Douglas Irwin, a Dartmouth College economist studying the history of trade policy, estimates that from 1790 to 1860, tariffs accounted for 90% of federal revenue.

The most infamous tariff act was the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which sharply raised tariffs before the Great Depression. Most economists don’t believe the increase in tariffs had a big influence on the Great Depression considering global trade was only 9% of GDP. However, one outcome of this tariff was the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934 which gave presidents authority to negotiate and update trade agreements and tariffs without approval from Congress.

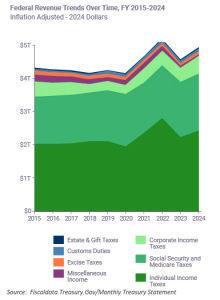

After the Great Depression and World War II, tariffs declined as global trade increased and as a result, they are now a meager source of revenue compared to individual income taxes, Social Security taxes, and Medicare taxes (shown in shades of green below). The chart breaks down sources of Federal Revenue for the last decade, with tariffs listed as “Customs Duties”. Note that even during the 2017-2021 period of the Trump presidency which saw new tariffs, they were still not a significant source of Federal revenue.

Are Tariffs a ‘sales tax’? Who pays the cost?

A tariff is not a ‘sales tax’ in the traditional sense. However, importers who pay the tariff typically raise prices to pass on the increased the cost of bringing goods to market to their end customers. Thus, tariffs result in higher costs on imported goods.

If Tariffs raise costs, what’s the benefit?

Tariffs protect domestic producers by making foreign goods less competitive and harder to sell.

For illustration, imagine a U.S. company that produces chocolate bars for $2.50 each competing with a Swiss company that produces similar bars for $2 each. A sweet-toothed President looking to protect jobs in the U.S. chocolate industry might decide that a tariff of 50% would be applied to all imported chocolate, effectively raising the cost of Swiss chocolate bars to consumers by $1 to $3/bar, making them the more expensive choice. This would likely lead to consumers buying American rather than Swiss chocolate bars.

Tariffs have frequently been employed in the past to combat unfair trade practices. For instance, if the Swiss government was subsidizing their chocolatiers to allow them to sell their bars for $0.50 each, a sizable tariff could help even the playing field. Foreign countries’ support of their manufacturing can take many forms: cheap credit, low wages, currency manipulation, and lax environmental laws can provide unfair advantages in trade.

Levying or lifting of tariffs can also be used to form strategic alliances. For instance, NAFTA (1994-2020) and its replacement policy USMCA (2020 – today) reduced barriers to trade across North America and established a process to handle economic disputes between the members. It also further extended U.S. influence beyond our borders.

What are the downsides of Tariffs?

Tariffs frequently lead to trade wars, where one country levies a tariff and in response the targeted country levies a tariff in return. For instance, in response to President Trump’s tariffs on aluminum and steel, the European Union taxed a variety of U.S. products such as bourbon and Harley-Davidson motorcycles. In a similar vein, China responded to Trump’s tariffs by adding their own tariffs to soybeans and pork, which hurt American farmers.

While a targeted tariff can help protect domestic businesses against a foreign rival, in cases where there is little to no domestic production, a tariff is often inflationary and results in higher costs without a meaningful economic benefit. For example, the U.S. continues to have a tariff on certain steel and aluminum products, yet the chart below from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics illustrates how the number of jobs in the steel industry in 2024 is virtually identical to what it was in 2018 and has trended significantly lower over time.

Tariffs are here to stay, but their impact is dependent on their application

The goal with tariffs is to reshape a trade imbalance and reduce unfair trade. Unfortunately, they are not a magic solution capable of halting the advance of foreign competition. For instance, many companies in targeted countries like China avoid tariffs by shipping goods through other countries like Vietnam or Mexico.

Tariffs will continue to be a part of American economic policy for the foreseeable future. However, this is not without risk. Since tariffs result in higher prices, they can slow the pace of progress when battling inflation.

Capital Markets

Equity markets were lower in October, breaking the pattern of five months of back-to-back gains. The All-Country World Index (ACWI) declined -2.2%, the S&P 500 declined -0.9%, while the EAFE retreated -5.4%. U.S. Small caps declined -1.4%. Emerging market equities fell -4.3%. U.S. Bond prices fell -2.5% for the month.