Given the recent volatility in the stock market, investors are left wondering about the potential disruptive effects of tariffs.

Douglas Irwin, a professor at Dartmouth, is a widely recognized as an expert on both historical and contemporary U.S. trade policy. He uses three R’s to summarize the history of tariffs in the US: Revenue, Restriction, and Reciprocity.

Prior to the establishment of federal income taxes, tariffs were used for Revenue. For the last 70 years, tariffs have generated approximately 2% of federal Revenue, but when the US was a pre-industrial society, it accounted for nearly 100%. During the Civil War, the addition of excise taxes on items like liquor, tobacco, and most retail goods helped to generate revenue in addition to tariffs. After the war, the revenue generated from the combination of excise taxes and tariffs created a surplus, allowing the US to pay off the war debt. After reducing government debt, Congress debated ways to increase economic growth by reducing taxes and tariffs.

Congress had two choices: lower the tariff rate, which would make imports cheaper, or raise the tariff rate to make imports so expensive that consumption declines and therefore the amount of revenue generated by tariffs would also decline. William McKinley, who would later become president, was chair of the House Ways and Means Committee in Congress and argued for the latter. Tariffs at these high levels fell in the category of Restriction, referred to as Protectionism at the time, since the goal was to protect domestic production.

In the short run, McKinley’s approach worked: prices rose quickly, and US industry filled in the gap left by foreign producers. The drop in imports reduced tariff revenue and alleviated the problematic surplus in federal revenue. McKinley won the presidency in 1896. He then shifted to using tariffs for the third R: Reciprocity. As part of a tariff package, Congress gave McKinley the authority to reduce tariffs selectively so he could use this as leverage to renegotiate trade agreements. By the end of his first term, economies around the world were beginning to boom and the US was so successful that it needed to expand surplus production to foreign markets. As a result, Protectionism was doing more harm than good.

President McKinley planned to reduce tariffs(1) but he was assassinated in 1901. Vice President Teddy Roosevelt then took office. Roosevelt wasn’t as focused on trade policy, and as a result, it took a decade before tariffs began to decrease after the establishment of the federal income tax system. In the years that followed, Reciprocity became a key bargaining tool, ultimately leading to free trade agreements.

Where are we now?

President Trump has described the goal of higher tariffs as encompassing all three Rs – raising Revenue, Restricting foreign competition, and using them as a tool for Reciprocity in trade negotiations.

This presents a challenge of balancing objectives, as all three cannot be accomplished simultaneously:

• If tariffs are to generate a significant amount of Revenue, they must be set at a modest level to still allow enough foreign goods to come in to be taxed.

• If tariffs are too high, their Restriction will result in a drop-off in consumption and therefore less Revenue.

• However, if tariffs aren’t high enough, the prospect of lowering them won’t provide leverage for trade negotiations, thus limiting the potential for beneficial Reciprocal agreements.

Since modern industrialized economies have supply chains with parts and materials from across the globe, high tariffs have the potential to be much more disruptive than McKinley’s day when the US was a relatively isolated nation. Thus, the confirmation of tariffs on Canada, Mexico, and China taking effect immediately with additional tariffs on other nations to come represents an upheaval of the existing trade environment. Since President Trump has made clear that he favors using tariffs as negotiating tools, it remains unclear how long they will be in place.

The near-term implications are:

- Businesses and investors may feel uncertain about how best to put capital to work. This uncertainty manifests in stock market volatility.

- Retaliatory tariffs from affected nations are inevitable.

- The immediate outcome will be higher prices for consumers and businesses in countries on both sides of a trade war, along with an increased risk of reinflation.

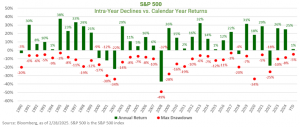

Historically, equity market volatility has been the norm

Every calendar year sees periods of market declines. History shows us that volatility is not a predictor of market returns, as illustrated in the chart below. Many of the downturns in the below chart have been caused by economic issues, political crises, wars, debt crises and even a pandemic. At the time, these situations may appear to be lasting disruptions to the US economy, prosperity, and investors’ ability to grow capital. It is difficult to see that short-term dislocations are just that – short-term.

Over time, American institutions have proven to be incredibly resilient and, indeed, the US has been the land of opportunity. As Warren Buffett said, “For 240 years, it’s been a terrible mistake to bet against America.”

The takeaway: Investors should remain patient and disciplined, focusing on long-term goals rather than short-term volatility.

Capital Markets

Equity returns in February were mixed. The S&P 500 fell 1.42%, the All-Country World Index (ACWI) declined 0.7%, and the Russell 2000 fared the worst, falling 5.45%. Meanwhile, developed international equities rose by 1.8% and emerging market equities increased by 0.35%. Bonds rose by 2.20%.

This document contains forward-looking statements, predictions and forecasts (“forward-looking statements”) concerning our beliefs and opinions in respect of the future. Forward-looking statements necessarily involve risks and uncertainties, and undue reliance should not be placed on them. There can be no assurance that forward-looking statements will prove to be accurate, and actual results and future events could differ materially from those anticipated in such statements.

(1) McKinley, the self-described “Tariff Man”, gave a speech in 1901 to a large crowd in Buffalo, New York saying “The period of exclusiveness is past. Reciprocity treaties are in harmony with the spirit of the times. Measures of retaliation are not. If perchance, some of our tariffs are no longer needed for revenue or to encourage and protect our industries at home, why should they not be employed to extend and promote our markets abroad?” McKinley assassinated the following day, died shortly after.